No Consensus in the Ripple Network

A technical analysis of Ripple’s protocol reveals that it ensures neither safety nor liveness under the stated assumptions.

Ripple consensus

Blockchain networks process and validate transactions without a central coordinator. They use distributed, fault- and attack-tolerant consensus protocols to achieve this. Whereas Nakamoto’s protocol in Bitcoin or Ethereum lets the nodes agree by an energy-hungry and slow proof-of-work, other systems like Tendermint, Hyperledger Fabric, or Libra use the permissioned model, with a defined set of nodes that vote on transactions. The latter follow the established algorithms for Byzantine-fault-tolerant (BFT) consensus from textbooks (such as this one) and process transactions extremely fast, but face criticism due to their permissioned nature.

The Ripple consensus protocol targets a middle ground between proof-of-work and BFT consensus by breaking up the common, global notion of a shared set of validator nodes. It lets every node declare other nodes it subjectively trusts in a so-called Unique Node List (UNL). A validator respects only the opinions of nodes in its UNL for validating transactions.

Ripple’s consensus protocol aims at ensuring that the same transactions are processed and validated ledgers are consistent across the network. It should protect the system against attacks and failure modes, such as malicious actors that may be attempting to control or interrupt the system at any given time.

Safety and liveness

A consensus protocol in a blockchain network must satisfy safety and liveness. Safety means that nothing “bad” ever happens: the ledger does not fork or and malicious participants cannot double-spend a token. Liveness means that something “good” happens over and over again, so that the network continues to process transactions and makes progress. Violating either property creates trouble for all participants in the network.

In a consensus overview from 2017, we have already pointed out that blockchain consensus protocols must be assessed formally. Unfortunately, many systems have been designed and were even deployed without following the scientific method of protocol design. Ripple is no exception to this, as we discuss here.

Ripple consensus fails badly

In our paper Security Analysis of Ripple Consensus that will be published at the OPODIS 2020 conference later this year, we investigate the Ripple consensus protocol. We give a detailed description of the protocol, suitable for assessing its properties at the level of scientific protocol research. No formal description of Ripple consensus with comparable technical depth has been available so far.

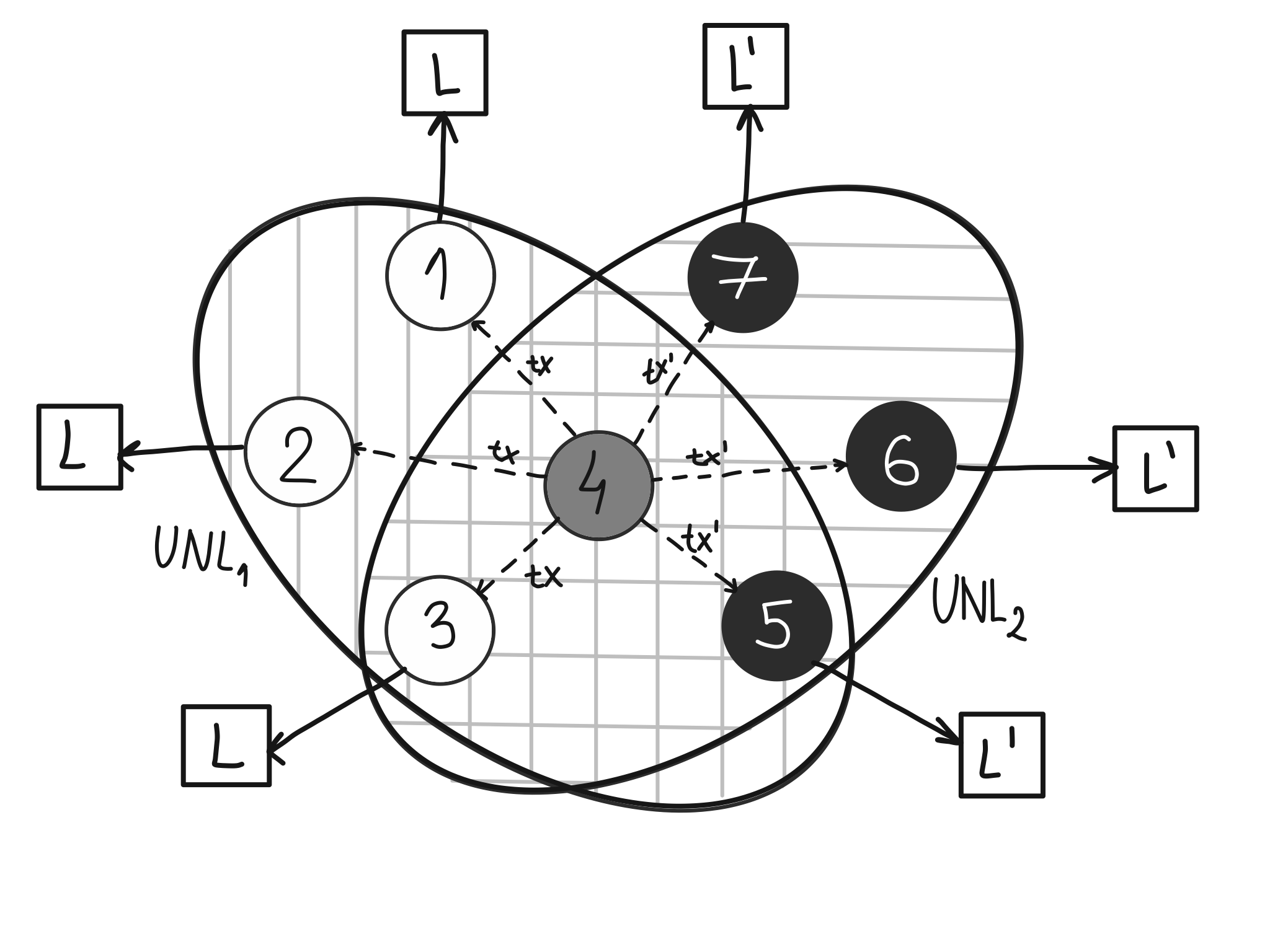

With the help of our model, we show that Ripple’s protocol does not achieve consensus and may violate safety and liveness, even under extremely mild adversarial conditions. In particular, the network may fork under the standard condition on UNL overlap stated by Ripple and in the presence of only a very small fraction of malicious nodes. The malicious nodes may simply send conflicting messages to correct nodes during a time when the network omits or delays messages among correct nodes. The following scenario, which is taken from the research paper and explained there, illustrates the problem of forking into separate ledgers L and L’ :

We also demonstrate how Ripple’s consensus protocol may lose liveness, even if all nodes have the same UNL and there is only one Byzantine node. If this would occur, the system has to be restarted manually.

Given these findings, we conclude that the consensus protocol of the Ripple network is brittle and fails to ensure consensus as commonly understood in computer science and among blockchain practitioners.

No decentralization

Recall that Ripple aims at decentralizing its consensus by letting each node select the validators it subjectively trusts through the UNL. One of our failure scenarios becomes possible because some nodes use a different UNL than others.

In the default configuration operating today, however, the Ripple company supplies the default UNL and recommends that all validators use it. We believe that all validators indeed follow this advice. Our findings also show that there are good reasons for insisting on such a centralized structure in the Ripple network. Namely, would nodes select the trusted validators on their own, consensus might be violated much more easily.

Consequences

So far, our attacks are purely theoretical and have not been demonstrated with a live network. But decades of research in computer security have shown that hypothetical attacks that were initially thought to be of academic interest only eventually make it into practice. Defenses must be established well ahead of that time.

Our findings show that the Ripple protocol relies heavily on synchronized clocks, timely message delivery, the presence of a fault-free network, and an a-priori agreement on common trusted nodes with the UNL signed by Ripple. If one or more of these conditions are violated, especially if attackers become active inside the network, then the system may fail badly.

If Ripple instead had adopted one of the standard BFT consensus protocols, which have been carefully described and analyzed in the scientific literature and are operating in blockchain networks today, then the network would not be exposed to such dangers.

Link to the preprint on arxiv.org

Response to discussions after first publication of this post

(added on December 10, 2020)

David Schwartz responded on Twitter that XRPL was designed to prioritize safety over liveness. But the established practice in the formal study of such distributed protocols requires to satisfy both, safety and liveness, because achieving one of them without the other, is useless.

In the standard models for proving consensus protocols, it is customary that (a) messages may be delayed arbitrarily and that (b) faulty nodes can send out conflicting messages. In the context of Ripple’s protocol, a less realistic model has been used:

-

messages among correct nodes must arrive timely, in contrast to (a).

-

assuming that every correct node always receives the same messages from faulty nodes, refuting (b). This is called “Byzantine accountability” by Chase and MacBrough [1].

In other words, every validator must in a timely manner receive every message sent, even if sent by a faulty validator with partial influence over the network. Protocols in this model are clearly less resilient than those in the standard model.

The requirement of 41% overlap between UNLs (using a quorum size of 80% of a UNL; by Chase and MacBrough [1], p. 13) uses this strong and unrealistic model. In the standard model, the requirements are higher.

Chase and MacBrough [1] assume 20% of nodes in a UNL may fail and show (Thm. 8) that if every two UNLs overlap by at least 90%, then the protocol maintains safety and does not fork. If more failures may occur, the UNLs must overlap even more. Recall a validator must choose via its UNL whom to trust: but its choices are limited by the required overlaps.

Our findings about safety violations are compatible with the bounds established earlier. As easily seen from our example violating safety, even when the UNLs of the white and black nodes overlap by 60%, then the ledger may fork.

In contrast, BFT consensus makes the standard assumptions (a) and (b), as done in Tendermint, Hyperledger Fabric, Libra and many others. Many formal proofs exist that these protocols achieve safety and liveness, with up to 33% arbitrarily faulty nodes.

Our earlier conclusion is confirmed: If Ripple would use one of the standard BFT consensus protocols, they would benefit from well-understood guarantees under clearly stated assumptions (no timeouts affecting safety) and better resilience to faults (33% instead of 20%). The downside is to use 100% UNL overlap, in Ripple’s terminology. But this would not change much from the assumptions of today. And it may be necessary anyway: in theory, 90% UNL overlap are required to guarantee safety in the existing analysis [1], and in practice, all nodes are supposed to download the same default UNL.

[1] Analysis of the XRP Ledger Consensus Protocol. Brad Chase, Ethan MacBrough, 2018.