Asymmetric Asynchronous Byzantine Consensus

We show how to realize randomized signature-free asynchronous Byzantine consensus with asymmetric quorum systems.

Consensus is arguably one of the most important notions in distributed computing and a key mechanism in blockchains. In permissionless blockchains, the miners act as participants in consensus protocols and operate in a trustless environment. Agreement is reached despite the absence of a shared and global model of trust in the system. Flexible and subjective trust models have therefore been studied in more detail, and consensus protocols based on these models have emerged.

Asymmetric distributed trust

Most protocols for consensus operate under the assumption that the number of faulty processes is limited and every process in the system shares this view. This means that trust has traditionally been symmetric, in the sense that all processes adhere to the global assumption about the number of faulty processes. Properties of protocols are guaranteed for all correct processes, but not for the faulty ones.

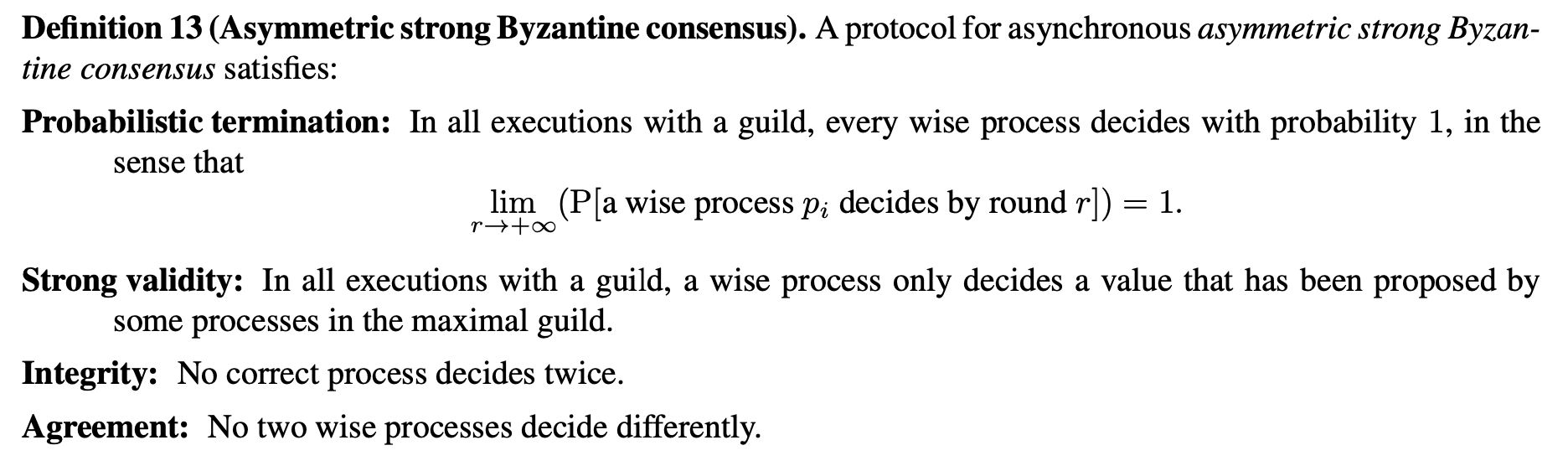

Blockchain networks, however, require trust to be more flexible because they do not assume global knowledge. Motivated by this desire, the Ripple and the Stellar blockchains introduced heuristic models for flexible trust. Cachin and Tackmann formulated asymmetric Byzantine quorum systems as a generalization of Byzantine quorum systems.

By abandoning a shared view of trust in the system, asymmetric quorums bridge the gap between the two main consensus protocol families used by blockchains and open up the possibility to implement consensus with asymmetric trust.

Asymmetric quorum systems expand on the notion of asymmetric trust introduced by Damgård et al. Every process in the system subjectively and individually declares who might fail in its own view. Depending on the choice that a correct process makes about who it trusts and who not, and considering the processes that are actually faulty during an execution, two different situations may arise. A correct process may either make a “wrong” trust assumption, for example, by trusting too many processes that turn out to be faulty or by tolerating too few faults; such a process is called naïve. Alternatively, when the correct process makes the “right” trust assumption, it is called wise. Protocols with asymmetric trust cannot guarantee the same properties for naïve processes as for wise ones.

Signature-free asynchronous Byzantine consensus

Mostéfaoui et al. presented at PODC 2014 a randomized, signature-free, and round-based asynchronous consensus algorithm for binary values, which achieves optimal resilience and takes O(n^2) constant-sized messages. Randomization occurs through a common coin as pioneered by Rabin. This binary consensus algorithm has been taken up for constructing the Honey Badger BFT, for instance.

Asymmetric Byzantine consensus

We have recently developed the first signature-free implementation of asymmetric asynchronous Byzantine consensus. Our protocol is randomized and takes up an algorithm by Mostéfaoui et al. with optimal communication complexity. This work will be published by CBT 2021 in connection with ESORICS 2021.

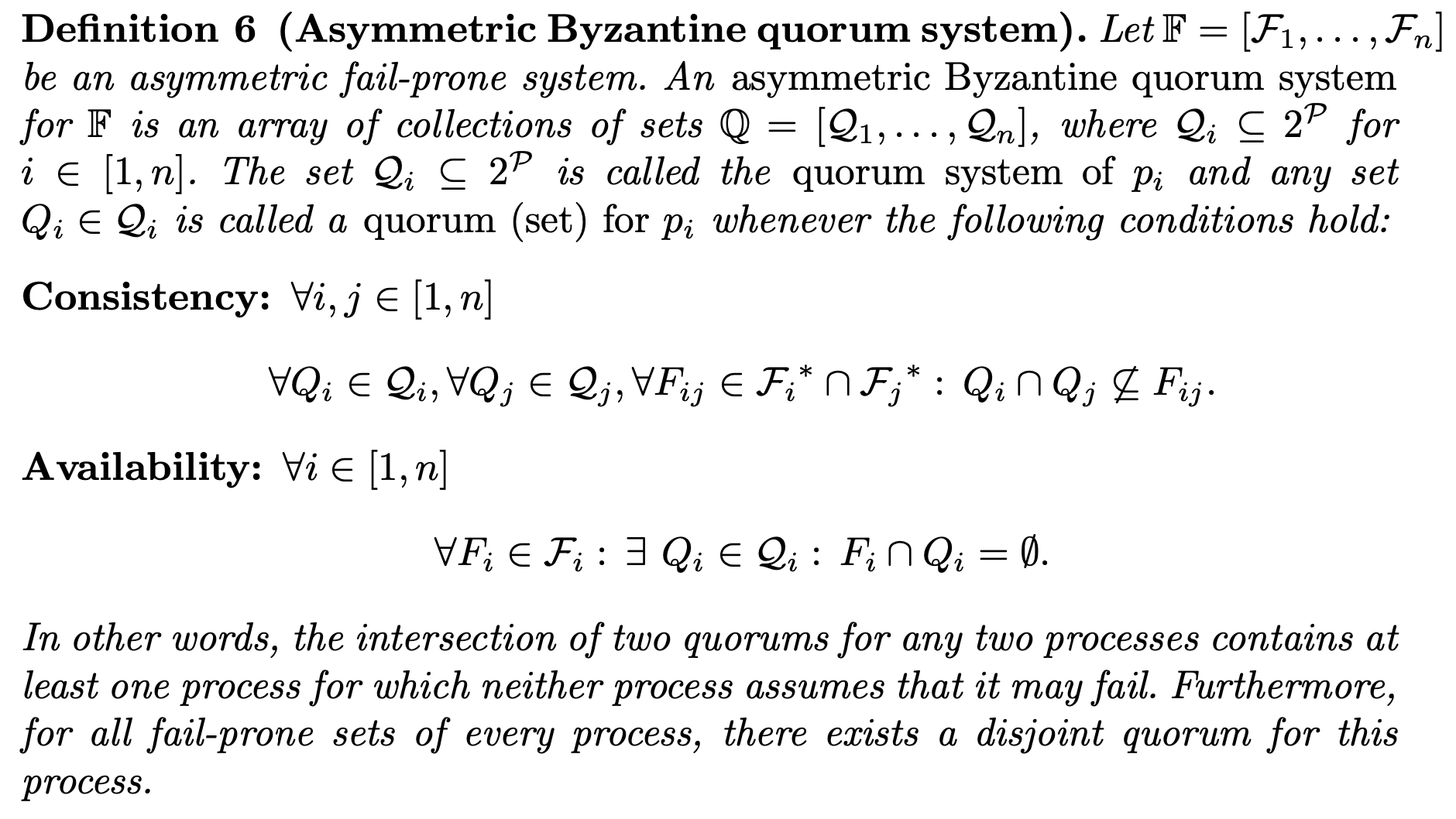

Our protocol implements strong Byzantine consensus in the asymmetric-trust model, according to this definition from the paper:

The validity property here only holds for wise processes. As we also show, the guarantees of consensus can only be given for wise processes. The existence of a so-called guild is also necessary for a protocol execution with asymmetric trust to terminate.

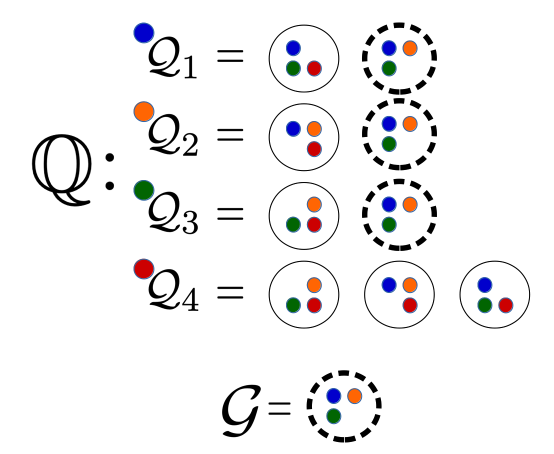

Recall that asymmetric trust means each process selects its own quorum system and thereby defines the quorums that convince it of the validity of some statement. A guild is a set of wise processes (who made the right choices) that contains at least one quorum for each member, that is, such that every member of the guild finds a quorum of processes for itself within the guild.

A guild among four processes P1, P2, P3, and P4 can be illustrated as follows. Each process has its own quorum system, Q1, …, Q4, each containing two to three subjective quorums for a process as shown by the circled sets. In this execution, P4 is faulty.

Notice that the set circled with a dashed line is a guild because it is a quorum for all correct processes (P1, P2, and P3) that are also in the guild.

To learn more, check out the preprint. The paper elaborates also on a little-known liveness issue in the original protocol of Mostéfaoui et al. We show there how this problem can be fixed in a simple way that retains the simplicity of the original approach from PODC 2014.