Consensus Beyond Thresholds

How does one express a trust structure for consensus in a distributed system that does more than counting possible faults?

Safety by numbers

The typical threshold assumption in systems based on replication (such as that at most f < n/3 nodes may fail) expresses safety by numbers. It works only if the nodes fail independently, without coordination or correlation. In real life, however, faults and system attacks often occur in a coordinated way and exhibit dependencies. Citing Amazon CTO Werner Vogels from his masterpiece Life is not a State-Machine: Many academics will confess to have made the assumption that failures of components are not correlated. This absolutely unrealistic assumption will come back to haunt you in real life, where failures frequently are correlated.

Expressing richer trust models

Orestis Alpos knows a better way than that. In recent work, we have shown how to run consensus protocols with generalized trust that respects dependencies and goes far beyond thresholds.

Consider a hypothetical organization with 16 members, jointly responsible for running a trusted system. To be concrete, think of approving transactions on a distributed ledger using blockchain technology, where members can have different functions and be trusted differently.

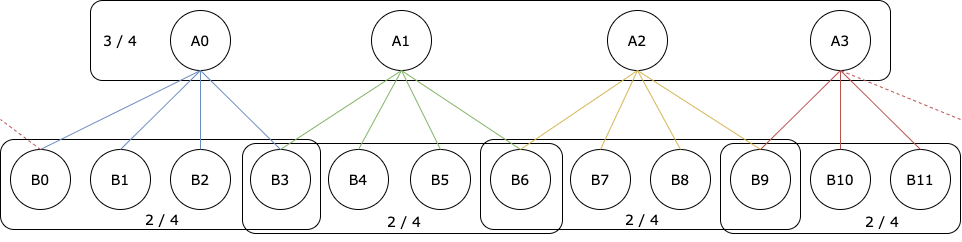

The organization consists of four areas and the members are structured in two layers. The members A0, …, A3 belong to the first layer, each responsible for one area, and B0, …, B11 belong to the second layer, in such a way that four of them are always responsible for one area. As shown in the figure, members B0, B3, B6, and B9 are responsible for two areas.

This trust structure takes the areas into account and requires everything to be approved by three of the four areas, where in each area the server in the first layer plus two out of the four servers in the second layer are required for approval. We call this a 2-layered-1-common (2L1C) Byzantine quorum system (BQS). It illustrates a hierarchical trust structure, where the members of the first layer are more important for approval and the members of the second layer are also not trusted equally, for example, because they are competent in two neighboring areas. This cannot be represented by a threshold.

For running a BFT consensus protocol under this assumption, we have to solve several problems:

-

How does the user specify generalized BQS compactly? The example here has 792 distinct minimal quorums.

-

How to encode the BQS internally? For instance, this could be done using a monotone Boolean formula (MBF) that uses threshold gates or a monotone span program (MSP), a linear-algebraic formulation of computation, which also characterizes all linear secret-sharing schemes.

-

How to efficiently test if a set of members is also a quorum? There are algorithms that depend on the representation chosen for the BQS, but their performance for practical trust assumptions is unknown.

Generalized HotStuff BFT consensus

In our paper, which appears at SRDS 2020 in September, we address these challenges and demonstrate that BFT consensus can run fast under generalized trust assumptions. We adapted the HotStuff Byzantine consensus algorithm to support generalized trust assumptions and evaluated its performance by means of benchmarks run over a datacenter network.

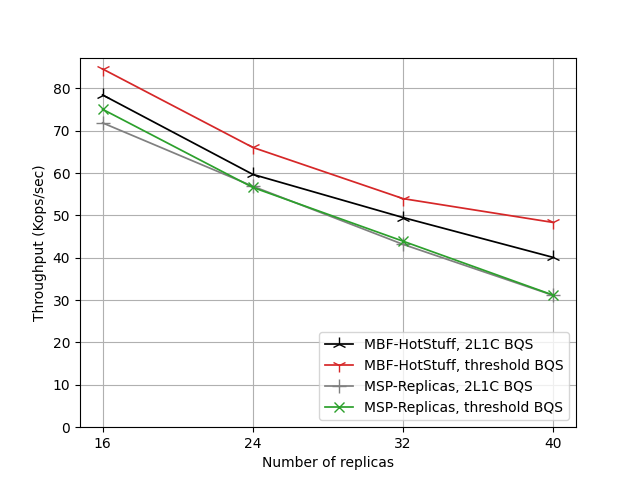

In one of our experiments, we compare these two encodings for two possible trust structures, namely the threshold BQS and the 2L1C BQS described earlier for 16 .. 40 members. The graph below shows the measured throughput in number of transactions (where MSP-Replicas stands for one of several implementations of MSP-based HotStuff):

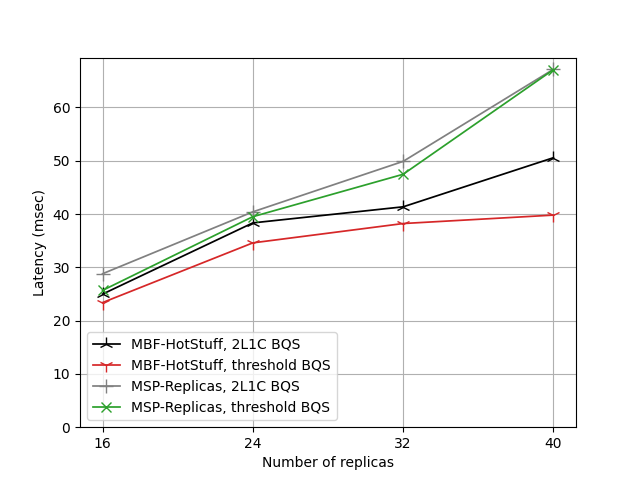

The evolution of latency in the same experiment is shown here:

One can see that with a threshold BQS encoded as a monotone Boolean formula (MBF), the system performs best (shown in red). The second-best performance is achieved by the MBF implementation of the 2L1C assumption (black). When span programs (MSP) are used, throughput decreases slightly while latency increases, showing similar behavior for the threshold BQS and for the 2L1C BQS encoded as MSP (shown in green and gray). The slowdown results from the additional matrix computations that take place internally for testing quorum properties in the MSP representation. The increase in latency of the MSP representation with respect to the MBF encoding grows as the number of replicas gets larger.

When interpreting these results, one should keep in mind that MSP and MBF are fundamentally incomparable representations of trust structures, because there exist functions requiring exponential-size formulas that can be encoded by a linear-size MSP.

We anticipate that our work paves the way for practical protocol implementations and deployments using generalized trust assumptions. More details about our work and the complete description of our results can be found in the technical report on arxiv.org.