Avalanche Consensus - Does it Perform as Promised? Part 2

In the second part of the series we take a look at the most basic Snow protocol, called “Slush”. We outline how this protocol works, including the effects of various network and tuning parameters on its performance, and give a rough sketch of our approach to analyze this protocol.

Part 2: Slush

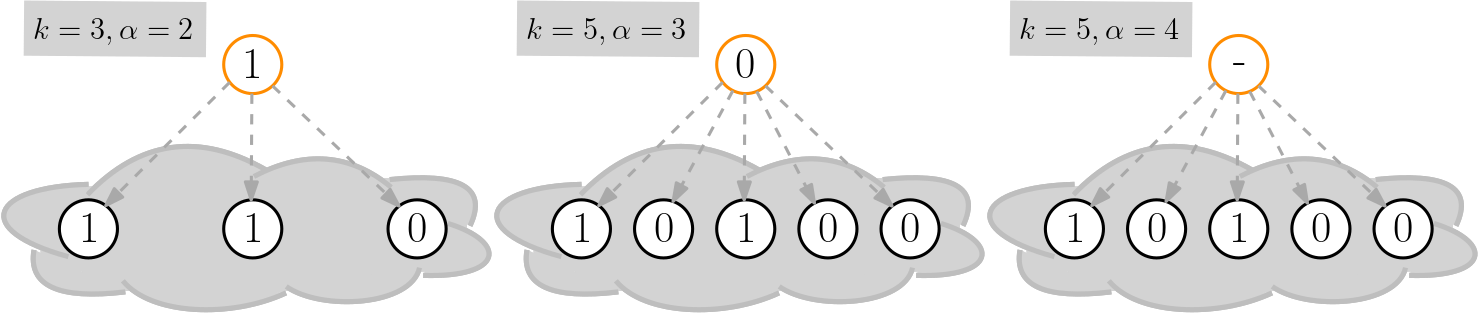

Let us go a bit further into detail. The simplest protocol that tackles the binary consensus problem is called Slush and works as follows. Each node continuously samples the opinion of \(k \geq 2\) others; if such a sample contains an opinion different from its own at least \(\alpha\) times (for some \(\alpha > k/2\)) then the node adopts this opinion as its own.

Here, we look at the slightly simpler binary consensus problem in which there are only two opinions, 0 and 1. We also assume that all nodes obtain their samples simultaneously in lock-step fashion, i.e., in synchronized rounds. It is however possible to reduce the more general consensus problem to its binary version and to weaken the assumption of synchronized rounds to a certain extent.

Three examples where the orange node samples a few others for different sample sizes \(k\) and thresholds \(\alpha\). In the first two pictures the orange node adopts the sampled \(\alpha\) majority. In the third picture there is no such majority and the node keeps its prior opinion.

Slush is a robust, self-organizing mechanism that is likely to converge to a stable consensus. This means that it reaches a state where a large majority of nodes have the same opinion relatively quickly and is very likely to remain there. This holds even in the presence of a limited number of Byzantine nodes.

Assessment of Slush in the Avalanche Whitepaper

The Avalanche whitepaper makes specific claims about the performance of the Slush protocol, which corresponds to the number of “rounds” until almost all nodes have consensus, where a round corresponds to each node making one sample. In general, the aim is that the number of samples each node has to make until such a state of almost consensus is at most logarithmic in the number of nodes \(n\).

This is rather fast, as the function \(\log n\) grows extremely slow in \(n\), proportional to the digits of the number \(n\). We often write \(O(\log n)\) for such a running time.1 Conveniently, a fast consensus also minimizes the number of samples and thus the messages each node has to exchange. The whitepaper gives informal explanations as well as an empiric study that can be seen as a proof of concept when the network, i.e., the number of nodes \(n\), is small.

The whitepaper’s claim about the asymptotic behavior, that is, the behavior for large \(n\), remains inconclusive. It also does not consider how other parameters such as the sample size \(k\) and the threshold \(\alpha\) influence the number of rounds to consensus. In fact, the complex interaction of performance with these parameters \(k\), \(\alpha\) and the randomized nature of the protocol makes the analysis of Slush quite challenging. This is the first open question that we answer.

Our Evaluation of the Performance of Slush

One concept that we found particularly useful in our analysis and is intuitive to explain is the expected progress that the system makes towards a consensus. It describes how fast the system is moving towards a consensus in one round. This progress essentially depends on how close we already are to such a consensus state as it affects the opinions that nodes are likely to see in their samples.

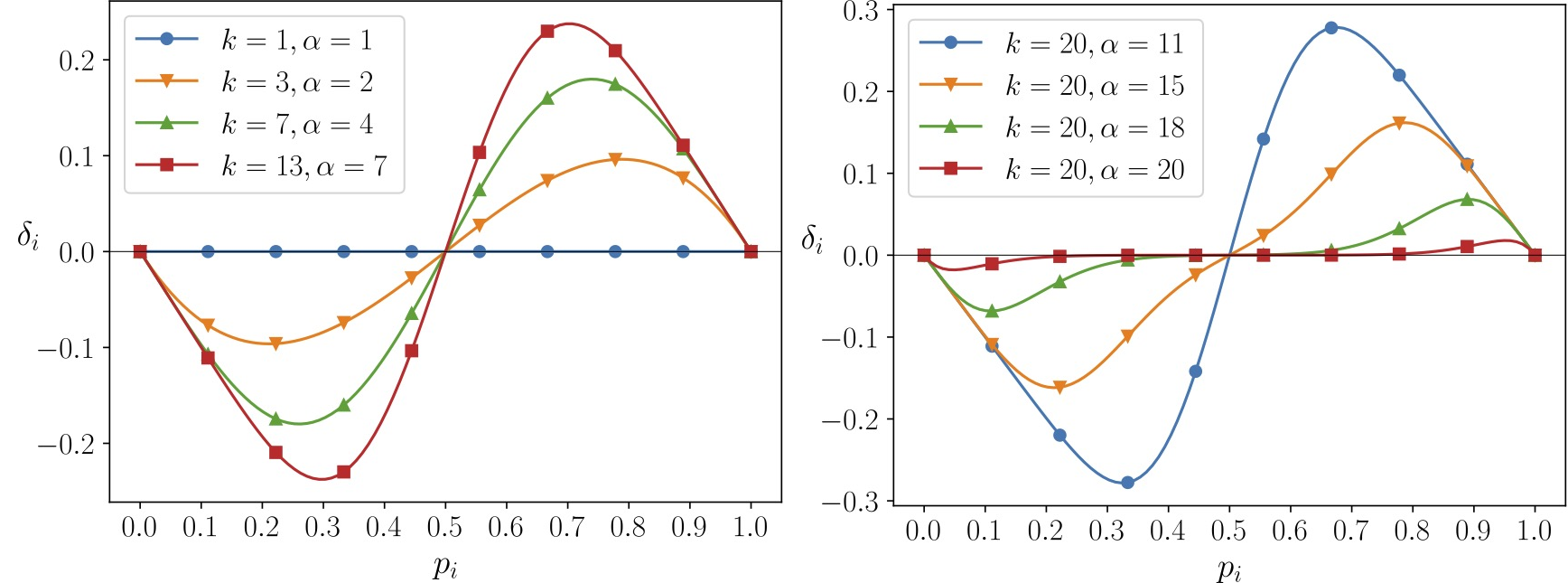

Assuming that \(k\) and \(\alpha\) are fixed constants, our analysis shows that the progress of the system can be expressed independently of the size of the network \(n\) as a function \(\delta(p_i)\), where \(p_i\) is the share of nodes that have opinion 1 in some round \(i\). That is \(p_i=0\) if all nodes have opinion 0 and \(p_i=1\) if all nodes have opinion 1.

The value of \(\delta(p_i)\) expresses the expected “step-width” that the system makes towards a consensus in round \(i+1\), i.e., a value \(\delta(p_i)= 0.1\) means that 10% more nodes are expected to have opinion 1 in round \(i+1\) than in round \(i\). Notice that \(\delta(p_i)\) is symmetric, and negative values of \(\delta(p_i)\) mean that the system is expected to trend towards a 0 consensus. The following plots show \(\delta(p_i)\) depending on \(p_i\) for a few different selections of \(k\) and \(\alpha\).

Plot of \(\delta(p_i)\) over \(p_i\) (ratio of nodes with opinion 1 and 0) for different values of \(k\) and \(\alpha\). Large values (in absolute terms) mean a large progress towards a consensus state is made. Positive or negative values of \(\delta(p_i)\) mean that the system converges to a 0 consensus or 1 consensus, respectively. Note that in certain situations (\(k=1\) and \(p_i=0.5\)) there is no expected progress is (\(\delta(p_i)=0\)).

What Can We Learn from the Expected Progress?

We can make a few immediate, interesting observations from the plots of \(\delta(p_i)\) shown above. First, the expected progress becomes larger as \(k\) increases and smaller the closer \(\alpha\) is to \(k\). From this we can conclude that increasing \(k\) has a positive effect and reduces the time to consensus. Further, it is always best for the expected progress to choose \(\alpha\) as small as possible (while still bigger than \(k/2\)).

The latter is interesting in light of the suggestion of \(k=20\) and \(\alpha=15\) by the whitepaper, which is suboptimal in that regard (we note that \(\alpha\) has a “dual purpose” in the whitepaper, where a value closer to \(k\) might arguably have some benefit for safety). Second, if the system is in a balanced state (\(p_i=0.5\)) or if \(k=1\), then there is no expected progress at all, i.e., in expectation the system stays right where it is.

In the perfectly balanced state (\(p_i=0.5\)), the step width \(\delta(p_i)\) is no longer useful to predict the progress. This is due to the fact this measure considers only the expected progress, whereas the real system behaves actually more randomly. In reality, it is likely that the actual change of \(p_i\) in the next round deviates somewhat from the expectation. Roughly speaking, it is fine to work with the expectation as long as the expected progress is relatively large.

However for \(p_i=0.5\) we instead need to rely on the variance of the random process to show that we will escape from the balanced state after a few rounds. This is also the state that is most vulnerable to malicious behaviour. In fact to be able to escape the balanced state makes it inherently necessary to limit the adversary to control at most \(O(\sqrt{n})\) nodes. Formal proofs of these observations and further insights into the properties of \(\delta(p_i)\) in particular the effect of \(k\) and \(\alpha\) are given in our paper. This ultimately allows us to derive the following two novel results about Slush.

- We show that the number of rounds until it is very likely that almost all nodes have the same opinion can indeed be upper bounded by \(O(\log n)\) rounds given that \(k > 2\) and \(\alpha\) is close to \(k/2\). This holds even if a limited number of nodes behave in Byzantine ways2.

- We show that the speed-up that can be obtained from increasing the sample size is at most \(\log k\) in expectation (formally we say that Slush has a lower bound of \(\Omega(\log n / \log k)\), where \(\Omega\) is a bound from below).

What Our Results Mean for Snow Consensus Protocols

We interpret these results in the following way. First, Slush indeed converges fast even for large \(n\). Second, increasing \(k\) yields only a limited speed-up of \(\log k\), whereas the number of exchanged messages increases directly proportional to \(k\). Therefore large values of \(k\), in particular values much larger than then the \(k=20\) suggested by the whitepaper, have diminishing benefit and an unfavorable trade-off in terms of message complexity.

Furthermore, we also show that the bounds for the running time above apply to Snowflake and Snowball, with an “asterisk”. More precisely, Snowflake and Snowball have an additional feature to finally decide an opinion and subsequently stop sampling. Roughly speaking, the analysis of running time holds for Snowflake and Snowball if that finalization does not take effect until the network comes close to a unanimous state. Furthermore, the finalization mechanics has significant effects, both intended and unintended and we will cover that in the final part.

Read more about Avalanche Consensus in part three of this blogpost.

-

\(O(\cdot )\) is called big-O notation or asymptotic running time and hides constant factors that do not grow in n. This measure is commonly used in the analysis of the behavior of an algorithm as the input size (here the size of the network \(n\)) becomes large. ↩

-

Our analysis for the upper bound is a generalization of a similar analysis that has been conducted for special cases of Slush called the 3-Majority, 2-Choices and Median protocols, the survey by Becchetti, Clementi and Natale provides a useful summary. ↩