Toxic Decoys: A Path to Scaling Privacy-Preserving Cryptocurrencies

Public blockchains such as Bitcoin and Ethereum are often referred to as transparent ledgers: every transaction is visible on-chain, and addresses can be linked through transaction graph analysis.

This openness enables independent verification of the integrity of the ledger, where transactions are recorded. However, it also means that anyone can trace the movement of funds between addresses. Over time, significant portions of a user’s financial history can be reconstructed, often linked to their real-world identity through off-chain information such as exchange records or merchant interactions.

To address these privacy concerns, several cryptocurrencies have been designed with privacy guarantees. Two examples are Monero and Zcash, which take fundamentally different approaches to hiding transaction details:

-

Monero uses linkable ring signatures to make each payment indistinguishable from a set of decoys. The sender proves that they own one of several possible outputs without revealing which one.

-

Zcash uses non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs to allow a sender to prove they own a coin among all coins that have ever been created in the shielded pool. This approach offers a larger so-called anonymity set than ring signatures, but usually comes with other compromises such as trusted setup requirements and computational overhead.

Although the cryptographic mechanisms differ, both approaches share a structural limitation: the ledger keeps growing indefinitely. Every transaction must keep track of all possible coins that could still be unspent, as well as additional cryptographic data to prevent double-spending, usually referred to as nullifiers. This constant accumulation increases storage requirements, slows down synchronization for new participants, and risks making the system less accessible over time as hardware requirements grow.

Understanding this scalability challenge, our recent work proposes a new perspective on this problem. Rather than treating storage growth as an inevitable cost of privacy, we examine how to reduce long-term storage without weakening privacy guarantees. Our approach involves reinterpreting a known privacy risk as a useful tool for system optimization.

The toxic-decoy problem

In ring-based systems like Monero, some decoys eventually become toxic—a term that describes outputs that lose their effectiveness as privacy protection due to logical deduction attacks.

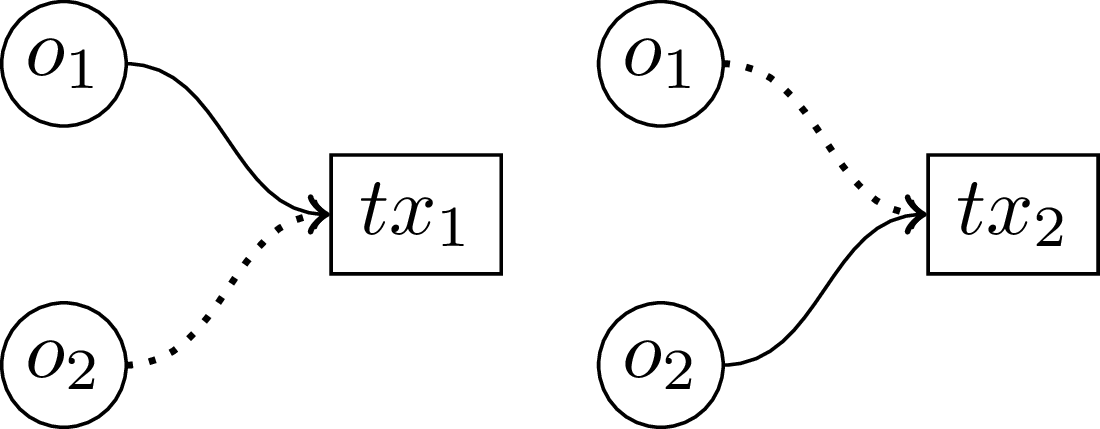

Consider two independent transactions illustrated below. The first transaction spends a coin called \(o_1\), while the second transaction spends a coin called \(o_2\). If \(o_1\) is used as a decoy in the second transaction, and \(o_2\) is used as a decoy in the first transaction, an observer analyzing the blockchain can make a joint deduction: both coins must have been spent somewhere, since each appears as a decoy in a transaction where the other is the real spend. However, the observer still cannot determine which specific coin was spent in which transaction—they only learn that both coins are no longer unspent. The situation becomes problematic when either of these coins is later used as a decoy in a third transaction. At that point, since their spent status is already known, they provide no privacy protection and could be removed from the anonymity set. This is why we call these outputs “toxic”—they become harmful to privacy since their spent status becomes deducible.

Two independent transactions where each real spend is also used as a decoy for the other. This mutual reference allows an observer to deduce that both coins have been spent.

Previous studies such as this one have examined how such toxic decoys reduce the privacy of ring-based systems. Building on this research, we ask a different question: if certain outputs will inevitably lose their privacy value and could theoretically be removed from anonymity sets, can we structure the system so that this removal becomes predictable, safe, and beneficial for scalability?

Known attack patterns

Before describing our approach, it helps to understand the types of attacks documented in the literature against decoy-based privacy systems. These attacks influence the design requirements of any improved system.

| Category | Attack type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Passive | Sampling discrepancy | If decoy selection does not match real spending patterns, an attacker can make statistical guesses about which output is the real spend. |

| Passive | Graph decomposition | By analyzing transaction graphs and removing toxic decoys, an attacker can reduce anonymity sets over time. |

| Active | Flooding | The attacker creates many outputs to dominate future anonymity sets and reduce the number of honest decoys per transaction. |

| Active | Pattern generation | The attacker creates outputs in ways that force predictable patterns, facilitating later deanonymization (e.g., dusting attacks). |

These attacks highlight two key requirements for any privacy system: it needs structural constraints on how decoys are chosen to prevent statistical analysis, and it needs randomness to limit adversarial influence over the decoy selection process.

Our approach

Our design addresses the known vulnerabilities by organizing outputs into bins—fixed-size groups that are formed at regular intervals called epochs. The key innovation is that binning is determined by a public and unbiased randomness source, ensuring that no party can predict or control the grouping in advance. This randomness is typically generated through verifiable mechanisms like distributed randomness beacons.

Binning mechanism

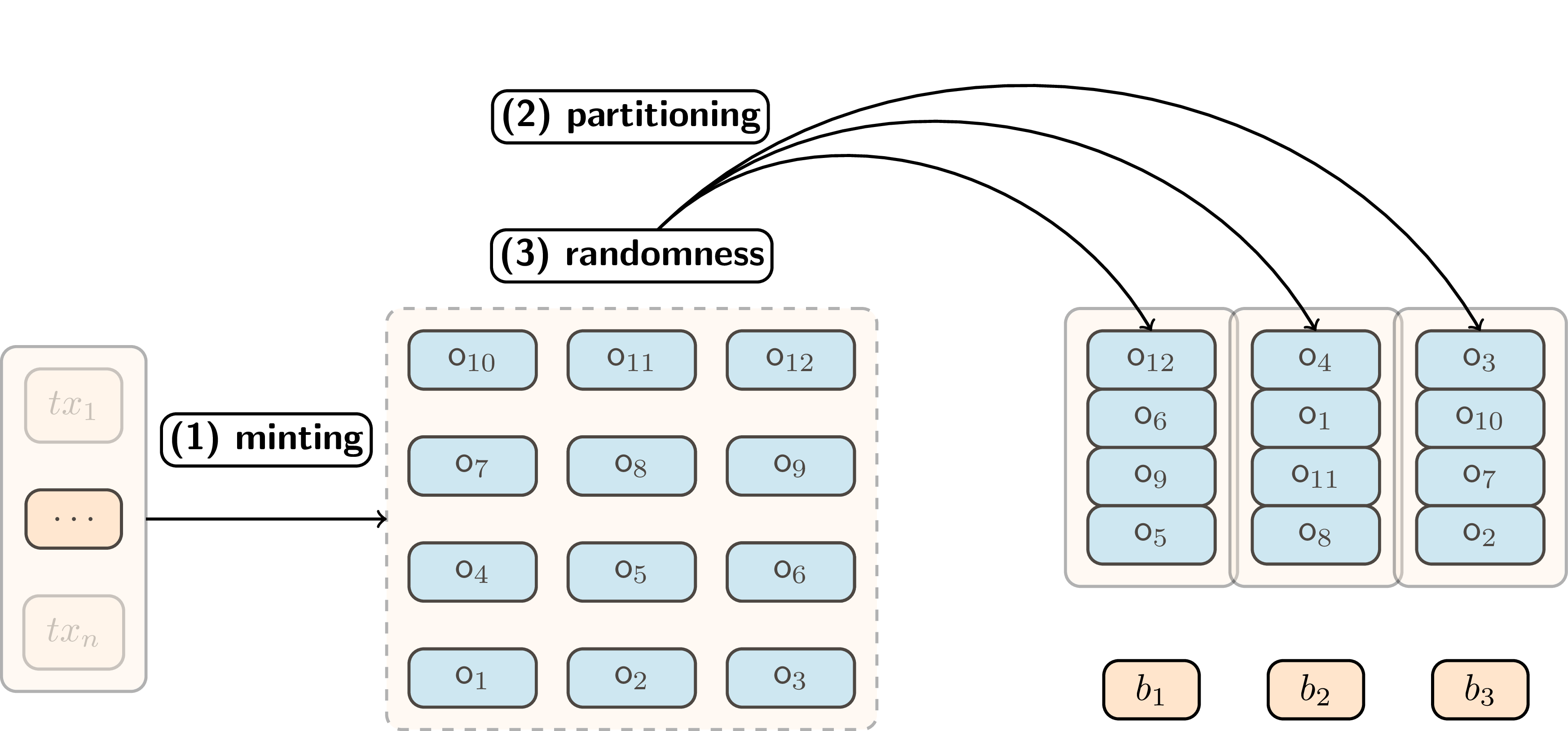

At the end of each epoch, all outputs minted during that period are collected and randomly assigned to a predetermined number of bins. Each bin contains exactly the same number of outputs, with the bin size chosen to balance privacy and pruning efficiency.

For example, if an epoch produces 800 new outputs and the system uses bins of size 16, these outputs would be randomly distributed across 50 bins. The assignment process uses the epoch’s randomness to ensure unpredictable placement that no participant can influence.

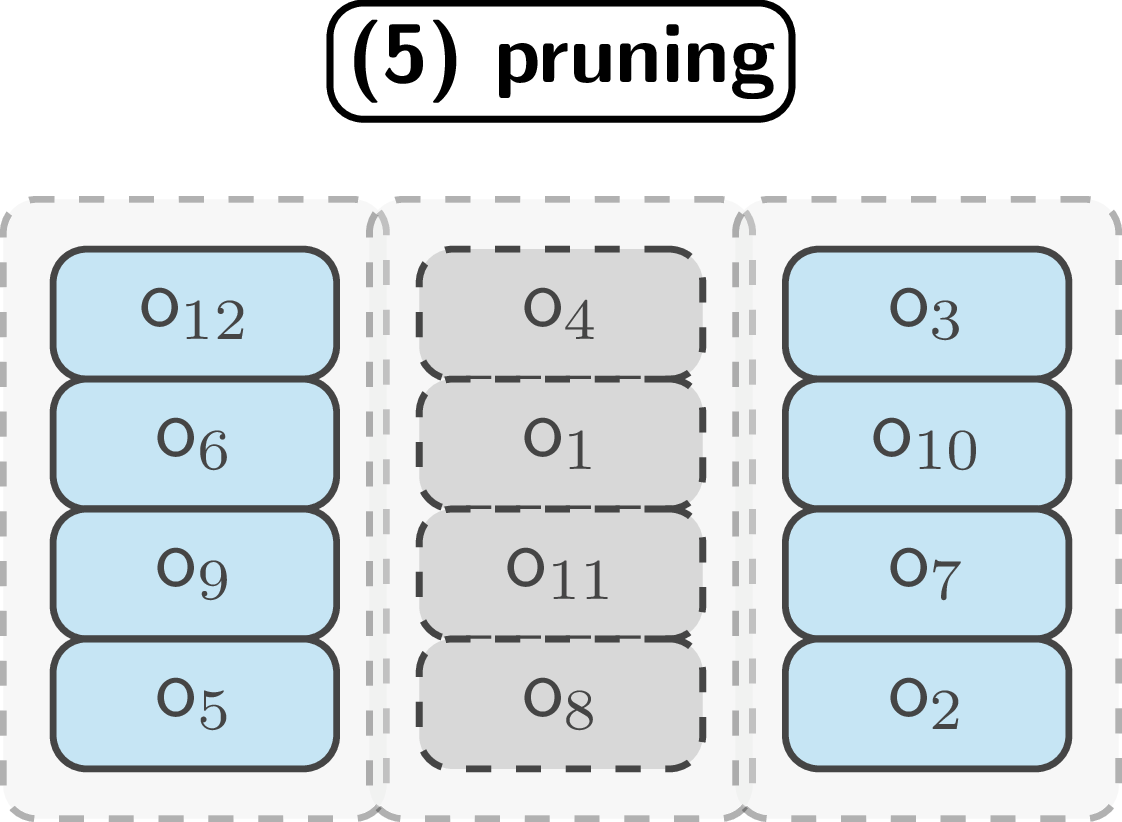

Outputs minted during an epoch are collected and randomly assigned to bins of equal size.

Transaction process

When making transactions, users must reference an entire bin rather than handpicking individual decoys. This fundamental change ensures that decoy selection follows the system’s randomization rather than potentially biased user choices. Users prove ownership of one output within the selected bin without revealing which specific output they control.

Each time a bin is referenced in a transaction, the system increments a usage counter for that bin. Once this counter reaches the bin size (meaning the bin has been referenced as many times as it contains outputs), the bin becomes eligible for pruning.

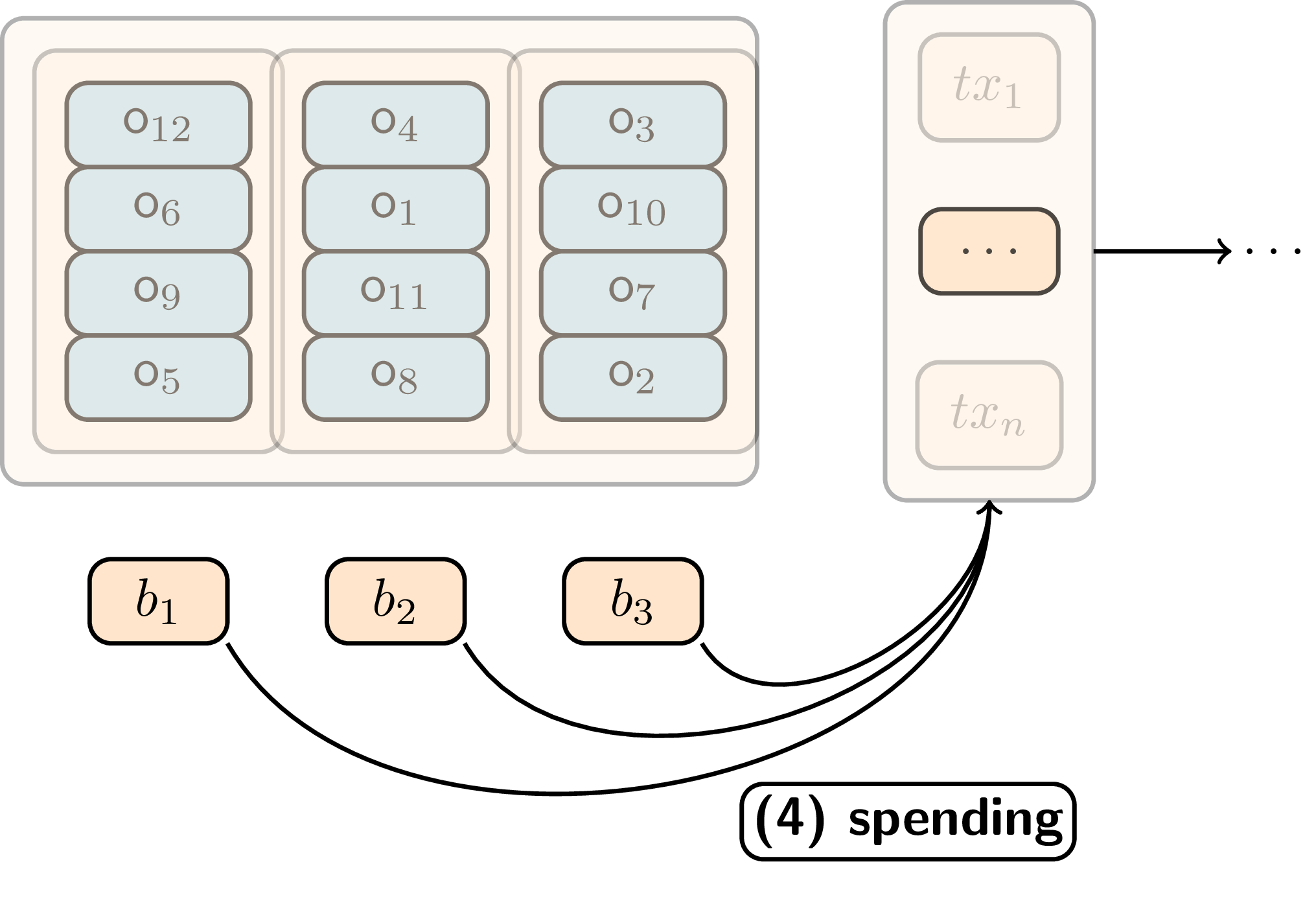

Users spend from bins by referencing the entire bin and proving ownership of one output within it.

Pruning and storage reduction

The pruning assumption works as follows: if a bin of size n has been referenced n times, then statistically, all outputs in that bin have likely been spent at least once. While this doesn’t guarantee every output was actually spent, it provides sufficient uncertainty that removing the entire bin doesn’t reveal which specific outputs were used in which transactions.

When a bin reaches its maximum threshold, the entire bin, including outputs and nullifiers, can be deleted from the active state. This pruning mechanism ensures bounded growth of the active ledger, as only bins still below their reference threshold need to be maintained by network participants.

Bins that have been referenced enough times are pruned from storage, reducing ledger size.

Attack mitigation

This approach systematically addresses the previously identified attack patterns:

| Attack type | Mitigation in our design |

|---|---|

| Sampling discrepancy | Periodic binning groups outputs created in the same time period, which tend to share similar spending patterns, reducing the statistical bias that enables this attack. |

| Graph decomposition | Once assigned to a bin, outputs remain in their group throughout their lifecycle, specifically preventing the toxic decoy problem. |

| Flooding | Random assignment spreads adversarial outputs across many different bins, limiting their concentration and capping their impact on any single anonymity set. |

| Pattern generation | Unpredictable placement of outputs prevents attackers from crafting specific transaction structures that could be exploited for later analysis. |

Construction

The bin mechanism can be implemented efficiently using Merkle trees, a well-established cryptographic data structure. Each bin corresponds to a Merkle subtree, where the leaves represent individual outputs contained in that bin. The root of each subtree serves as the bin’s unique identifier and is used in transactions instead of explicitly listing all outputs.

When a user wants to spend an output from a bin, they provide a Merkle membership proof demonstrating that their output belongs to one of the bin’s leaves. Crucially, this proof does not reveal which specific leaf contains their output, preserving privacy within the bin.

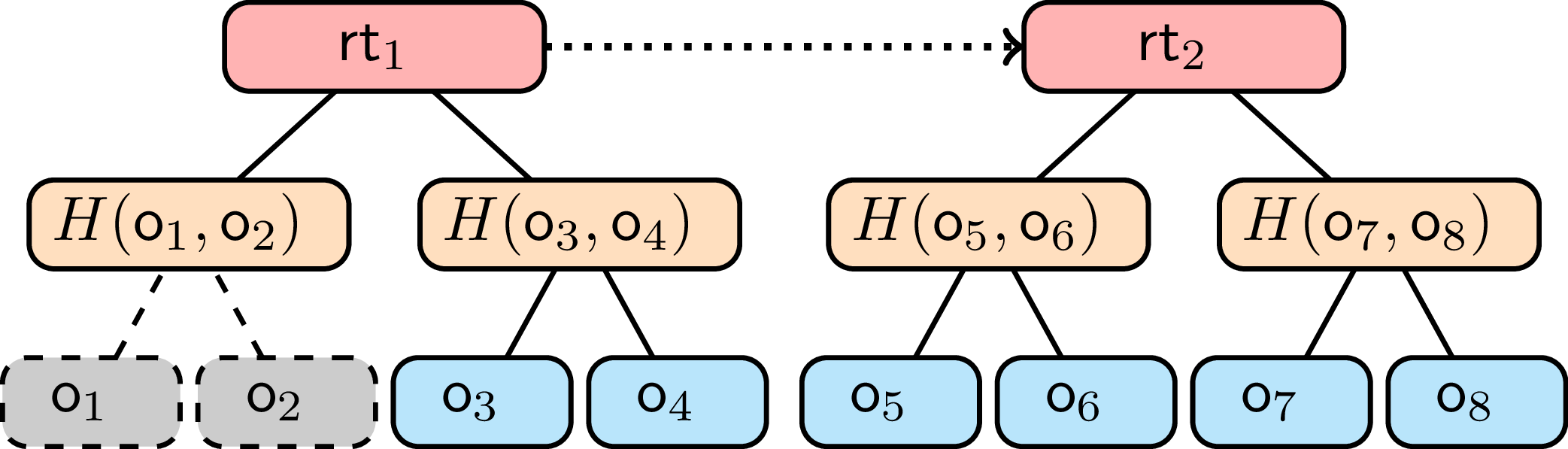

Two epochs represented as Merkle trees, with bin containing \(o_1\) and \(o_2\) meeting the pruning condition and being removed from the active state.

When a bin meets the pruning condition (having been referenced enough times), the entire Merkle subtree and its associated nullifiers can be deleted from storage. This design has the advantage of being completely agnostic to the underlying proof system, making it adaptable to different privacy-preserving cryptocurrencies.

Evaluation

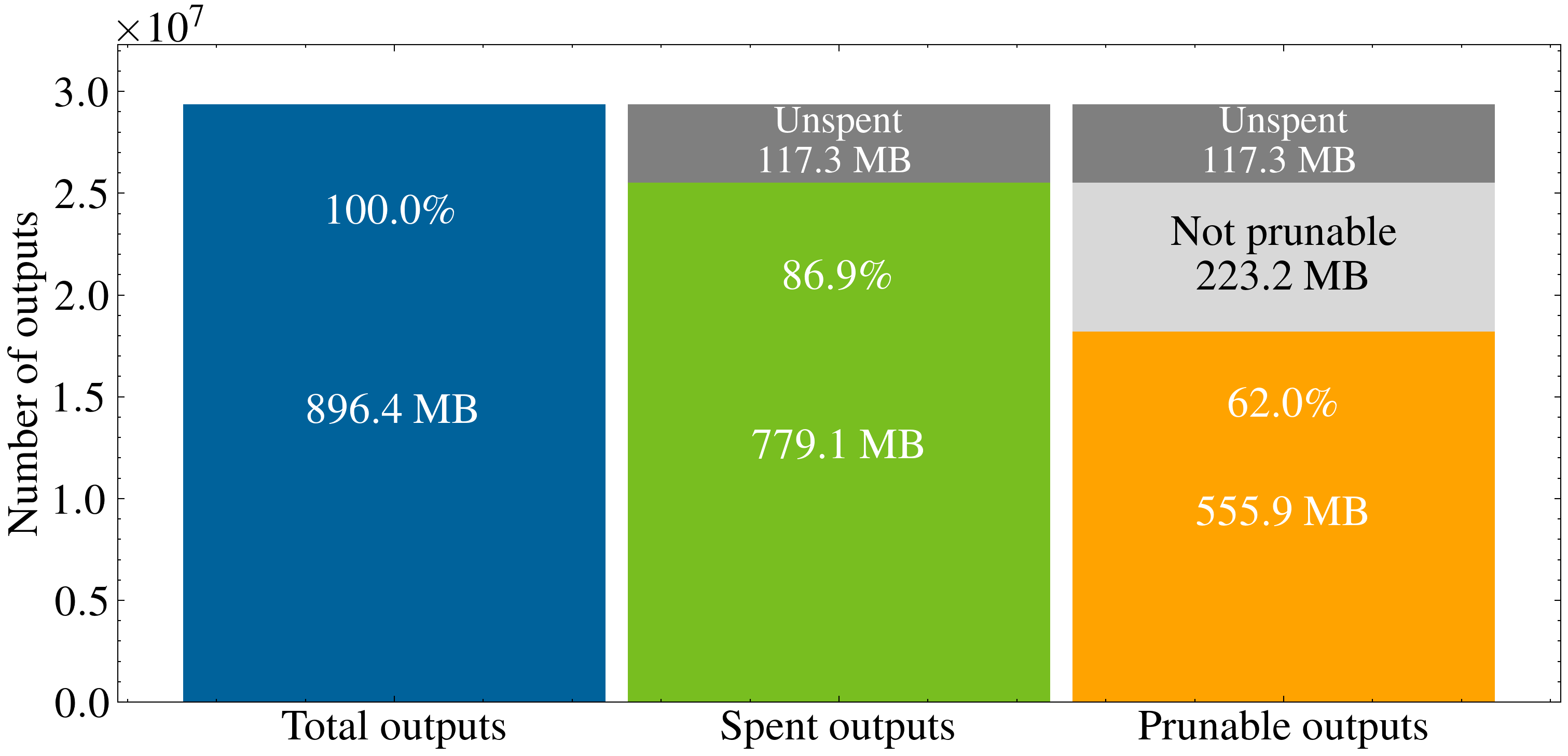

We evaluated our scheme using real-world data from Monero transactions spanning a full year from May 2024 to April 2025. The simulation covered 52,530 epochs, with each epoch representing a 5-block interval. Throughout the simulation, we dynamically adjusted the number of bins per epoch to maintain anonymity sets at a minimum level of 16 outputs, ensuring that privacy protection remained consistent.

Results showing the pruning ratio at the end of the simulation.

The evaluation demonstrates that our pruning mechanism reduced ledger size by approximately 60% over the test period. Additionally, transaction sizes decreased because bin identifiers require less space than explicit decoy lists. Throughout this storage reduction, privacy levels remained the same as in the original transaction set, confirming that the approach successfully balances efficiency with security.

Privacy-scalability trade-off

This design naturally creates a balance between the size of each anonymity set and the speed at which bins can be pruned from storage. Larger bins offer greater anonymity because they contain more potential outputs to hide among, but they also take longer to be fully referenced and thus require more time before pruning becomes possible.

Conversely, smaller bins can be pruned more quickly, leading to faster storage reduction, but may contain fewer honest outputs in case of a flooding attack. This reduction in honest outputs can weaken anonymity if an attacker controls a significant fraction of the outputs in the system.

The random assignment mechanism plays a crucial role in managing this trade-off. By distributing outputs unpredictably across bins, the system limits how many outputs an attacker can place in any single bin. This constraint allows system designers to choose bin sizes that achieve both meaningful privacy protection and efficient pruning without being overly vulnerable to adversarial manipulation.

Deployment and applicability

The binning mechanism can be integrated into existing privacy-preserving cryptocurrencies, though the implementation approach varies depending on the system’s current architecture:

-

Monero integration: The system could replace its current explicit decoy lists with bin identifiers and Merkle proofs. This would require adding a randomness generation mechanism synced with the consensus layer to ensure unpredictable bin assignments, but the core ring signature approach would remain largely unchanged.

-

Zcash integration: Implementation would require more substantial changes to the system architecture. Currently, Zcash allows users to prove ownership over coins from the entire shielded pool. Restricting this to individual bins would reduce the anonymity set from all existing coins to just those within a bin, introducing a more pronounced privacy-scalability trade-off that would need careful consideration.

The choice of integration approach therefore depends on each system’s specific requirements for privacy, performance, and compatibility with existing infrastructure.

Conclusion

Our approach demonstrates how a known privacy vulnerability can be transformed into a practical tool for addressing the challenge of long-term scalability. By organizing outputs into randomized, prunable bins, the system can bound ledger growth without undermining the privacy properties that users depend on.

Our evaluation using real transaction data confirms that the approach can achieve meaningful storage savings. The results show a 60% reduction in storage requirements while maintaining consistent privacy guarantees throughout the evaluation period.

These findings suggest that our approach represents a viable path for scaling privacy-preserving cryptocurrency systems without compromising their core security models. The approach offers a way to manage the storage growth that has long been considered an inevitable cost of strong privacy protection.

For more information, check out the full research paper.

This work is part of our interdisciplinary research project on Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) and has also been supported by the Initiative for Cryptocurrencies and Contracts (IC3).